The recent revival of photography books has allowed many photographers to find an outlet for their work. Despite a number of fine landscape photography books in print, the majority of publishers prefer to publish narrative projects often with portraits as part of the series.

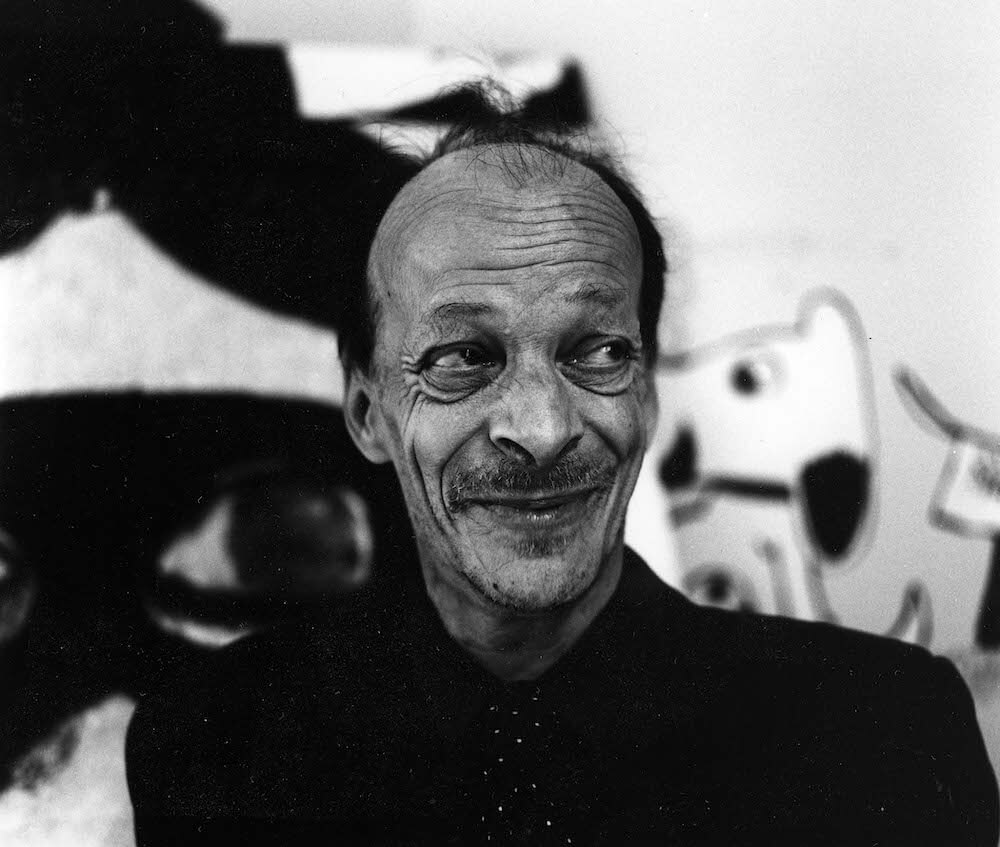

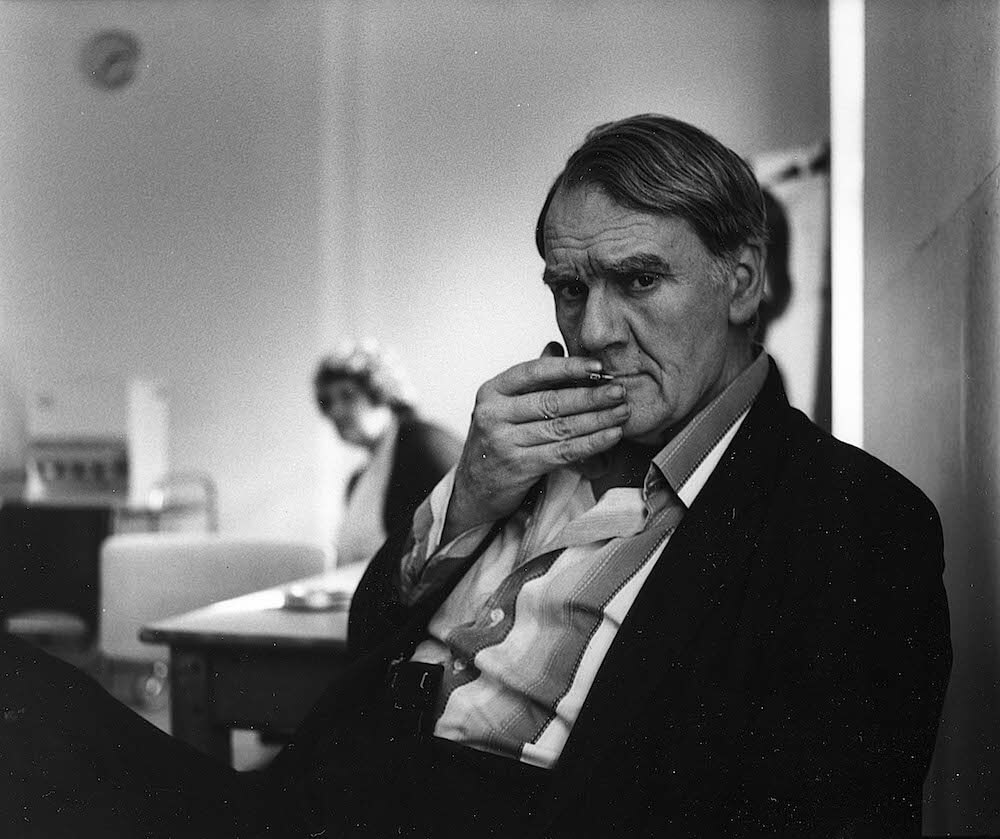

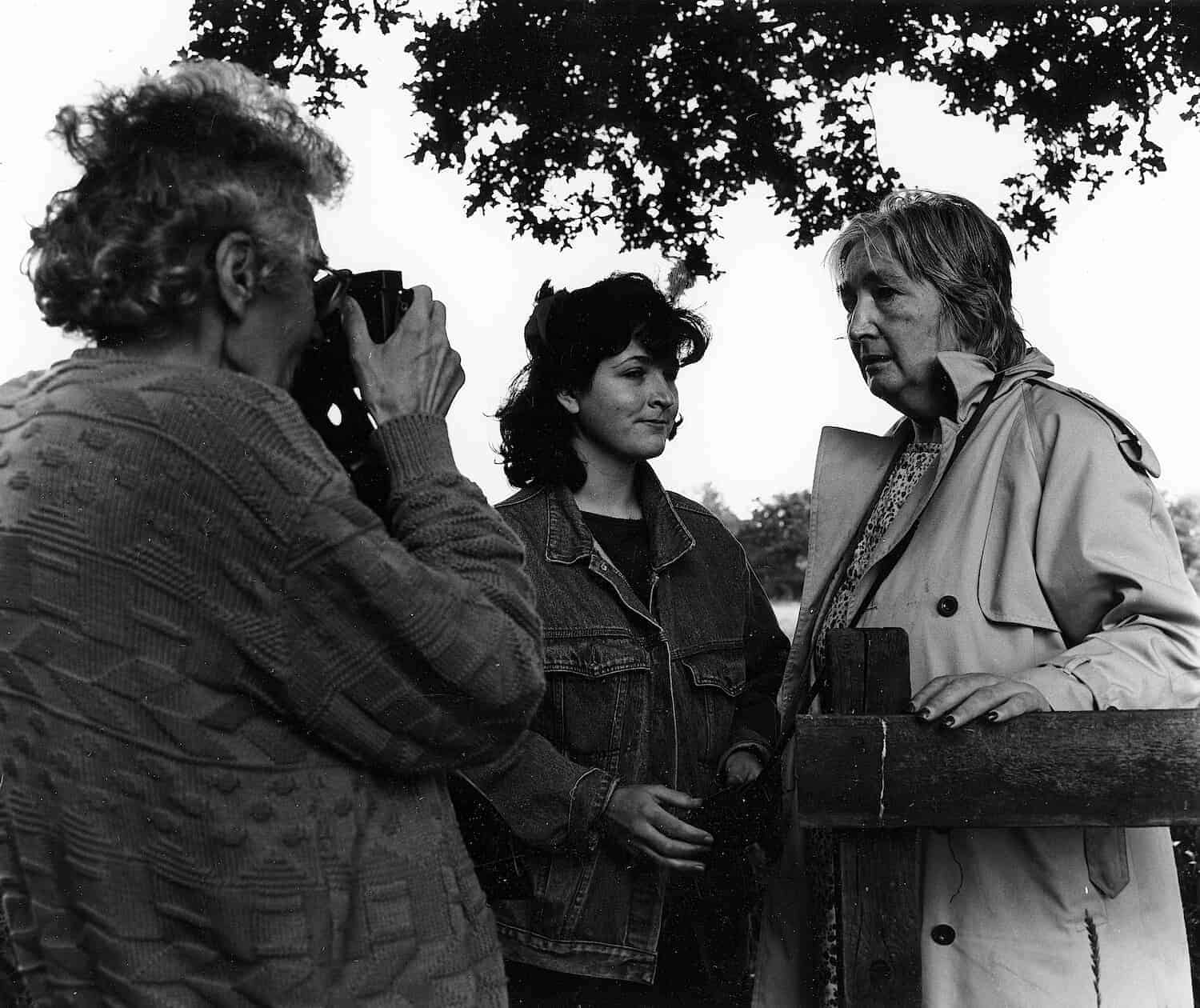

It could be argued that photography’s main draw is images of people, either as the main subject or interacting with the world around them, creating events. The narrative is often the term used to describe what’s happening in these scenes and it’s a word that is worth defining here as it is often misused, mistakenly interchanged with the story.

Narrative and story are not the same things. Whilst a story has a narrative, a narrative is not automatically a story. If we consider the narrative in cinema, we can say that most mainstream films incorporate a story, directing the viewer to one place; a closed narrative. In photography, minus actors, sound, script and music, it’s difficult to produce something so explicit. In books and exhibitions using a sequential format, a series of photographs can at best achieve a half story.

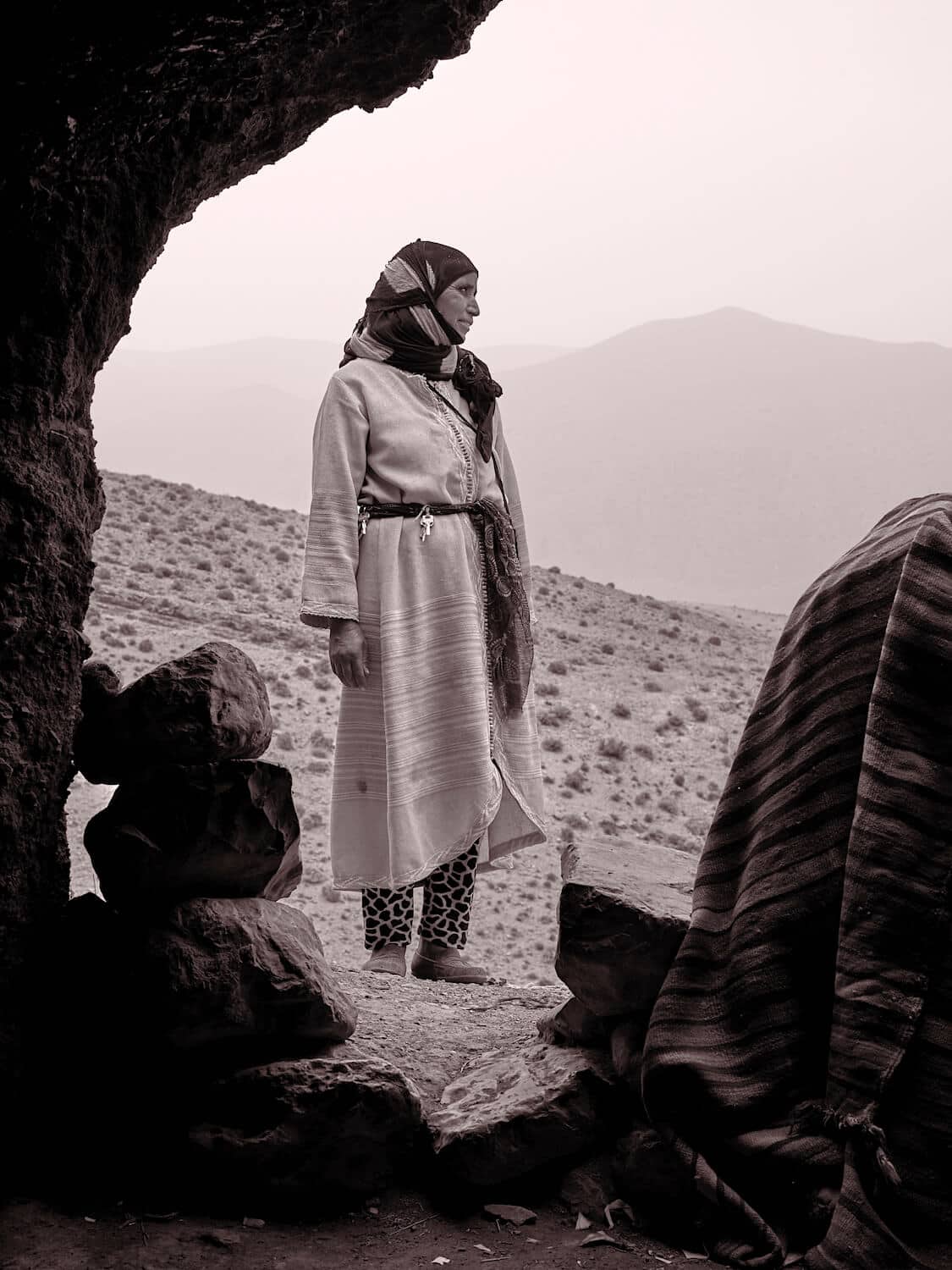

This half story can be found in the work of Gregory Crewdson. His images demand the viewer to bring cultural associations to the staging, lighting and compositions upon which we base our interpretations. It’s within us to read a narrative based on the culturally influenced schemas that we use to view photography.

One theory states that single images can never offer a narrative but even Crewdson’s photos viewed as singles, are still layered with meaning. Overall, Crewdson is not directing us to one specific universal understanding of the images but allowing individual interpretation. Across a series, the connections between one picture and another are elusive and open-ended, a perfect example of a ‘half story’ or an open narrative.

We can say that story is closed with clear narrative intent, which is unlikely to be found in most photographic works including Crewdson’s, by nature of the medium (a frozen moment in time). Instead the narrative, open, elliptical with free associations is more commonplace, and perhaps where photography uniquely resides.