Portraiture as a distinction from street photography is best defined through its relationship to the subject. If you as the photographer have the time to craft a shot with the consent of the subject, then it could be considered a portrait irrespective of the location and context. That craft time can be short, perhaps a minute (see project) or substantial over a couple of hours.

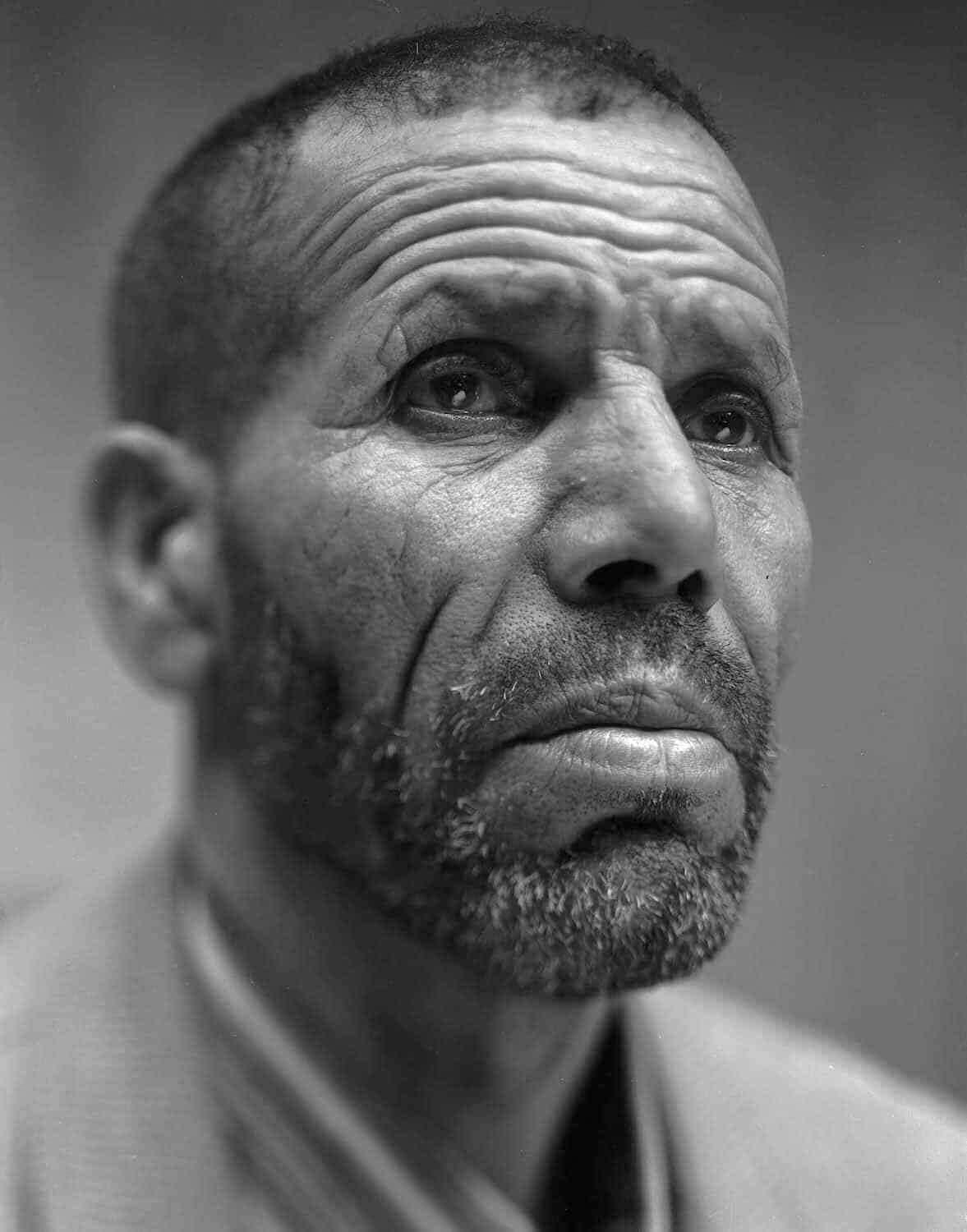

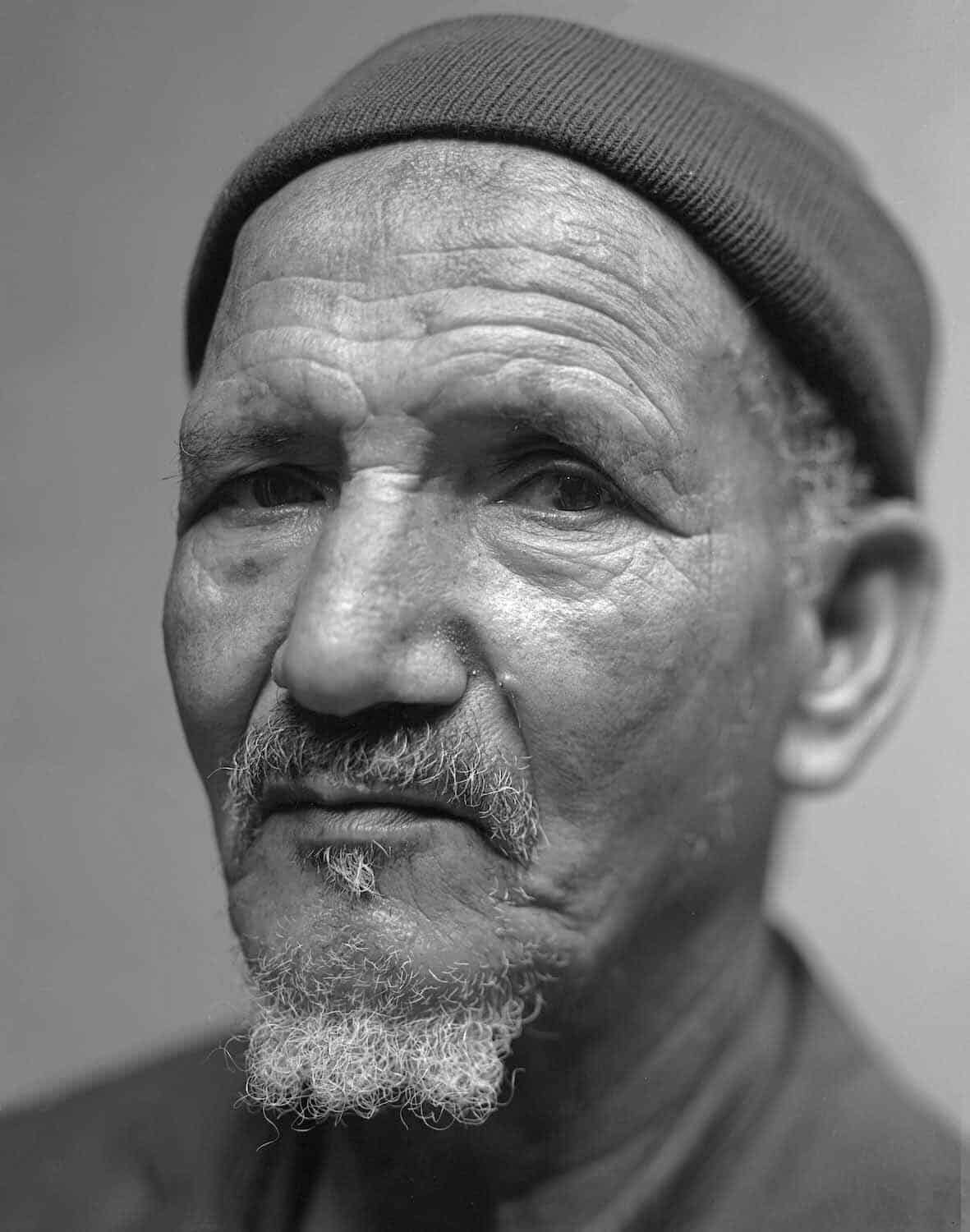

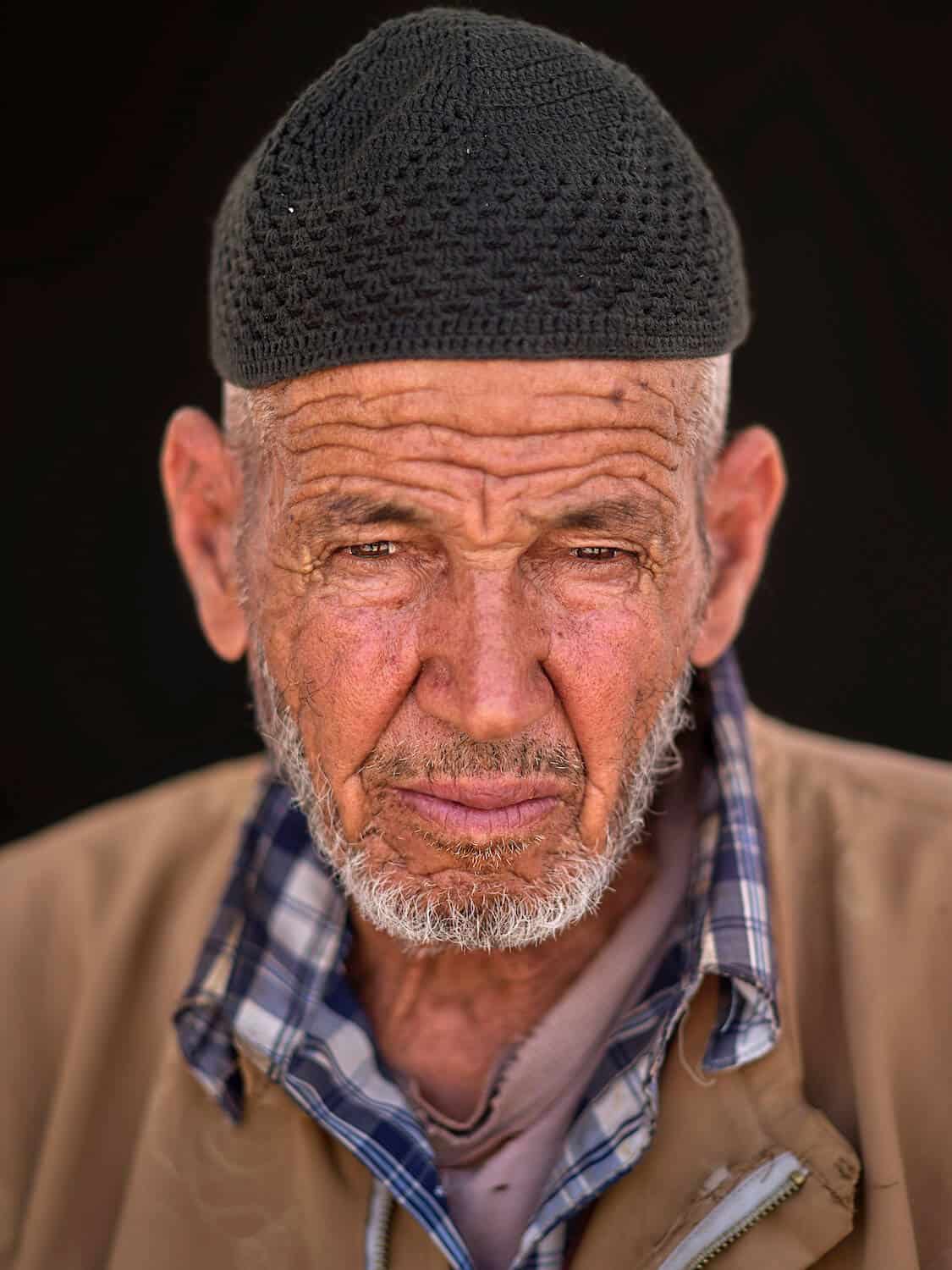

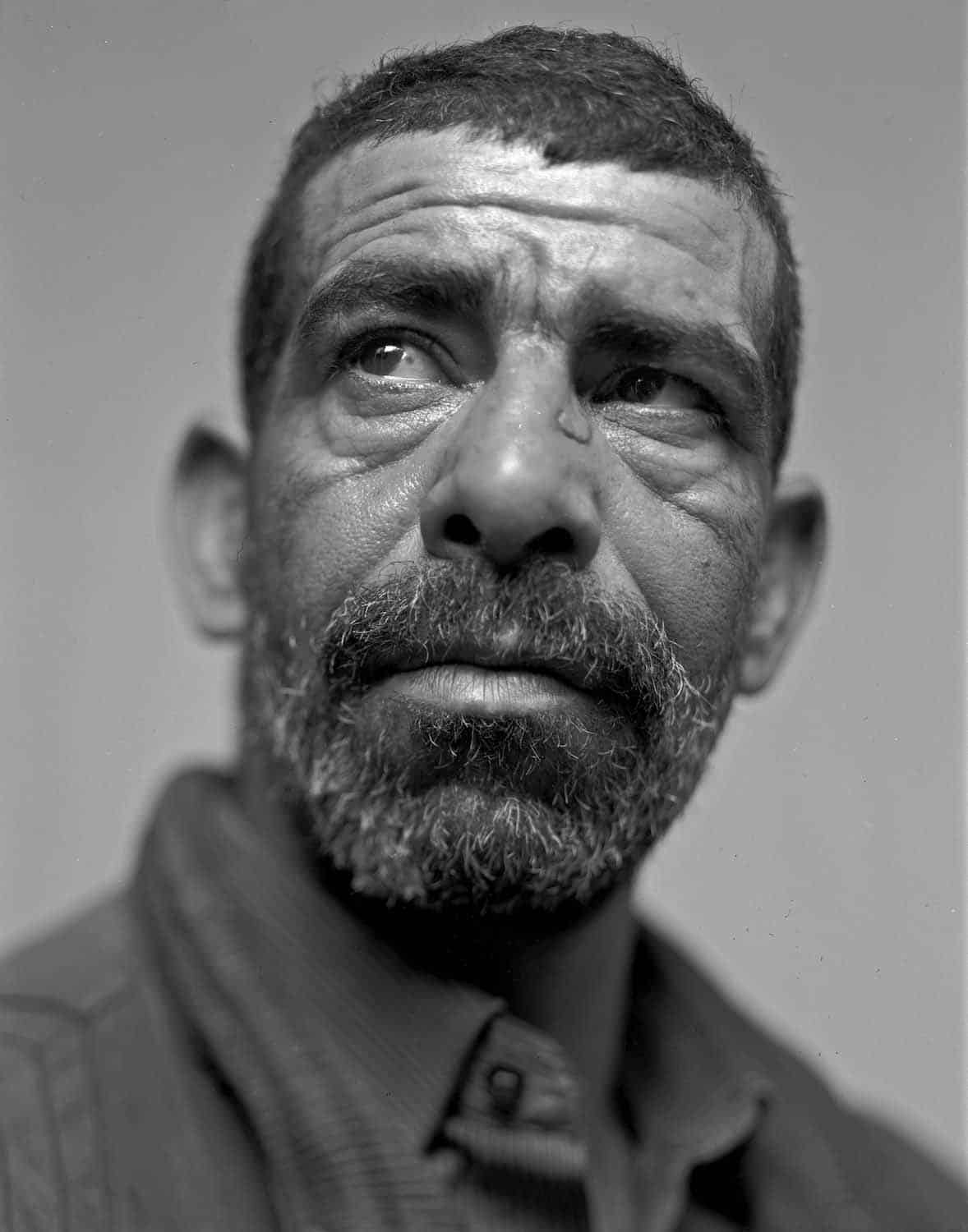

The range of portrait approaches since the origin of photography has remained relatively standardised. As a viewer, we are primarily drawn to a subject’s expression, pose or context, which as a photographer can feel limiting or challenging depending on your intentions. World-class images can move us off course, take Steve McCurry’s portrait of the Afghan girl, and shift a career to new heights. Often success is not so much through design but through the sitter’s charisma that the photographer intuitively senses. In the best images, it can be a fleeting moment that no amount of photographic genius can engineer, or perhaps a stillness which is easier to create and offers a psychological dimension.

Much of contemporary portrait work requires the viewer to understand its context; why indeed is this person important. If we separate models as portrait subjects from subjects who are chosen for other reasons, then this contextual framing becomes essential, especially so when just one image is presented to us.

In approaching portraits we can use six areas to help shape what we are trying to achieve.