For those starting off in photography, the task is mainly looking for content and to compose that in the best way possible. With good composition the aim, it’s rarely understood that to make a strong photograph, an interesting scene or subject requires the photographer to find and reveal its form. ‘Compositional rules‘ are often discussed as a means to help make a photograph ‘work’ but it’s rarely noted what the arrangement of the scene’s elements is. Distinguishing between form and compositional form should be our starting point.

“The contest between content and form – that’s the problem you state.” Gary Winogrand.

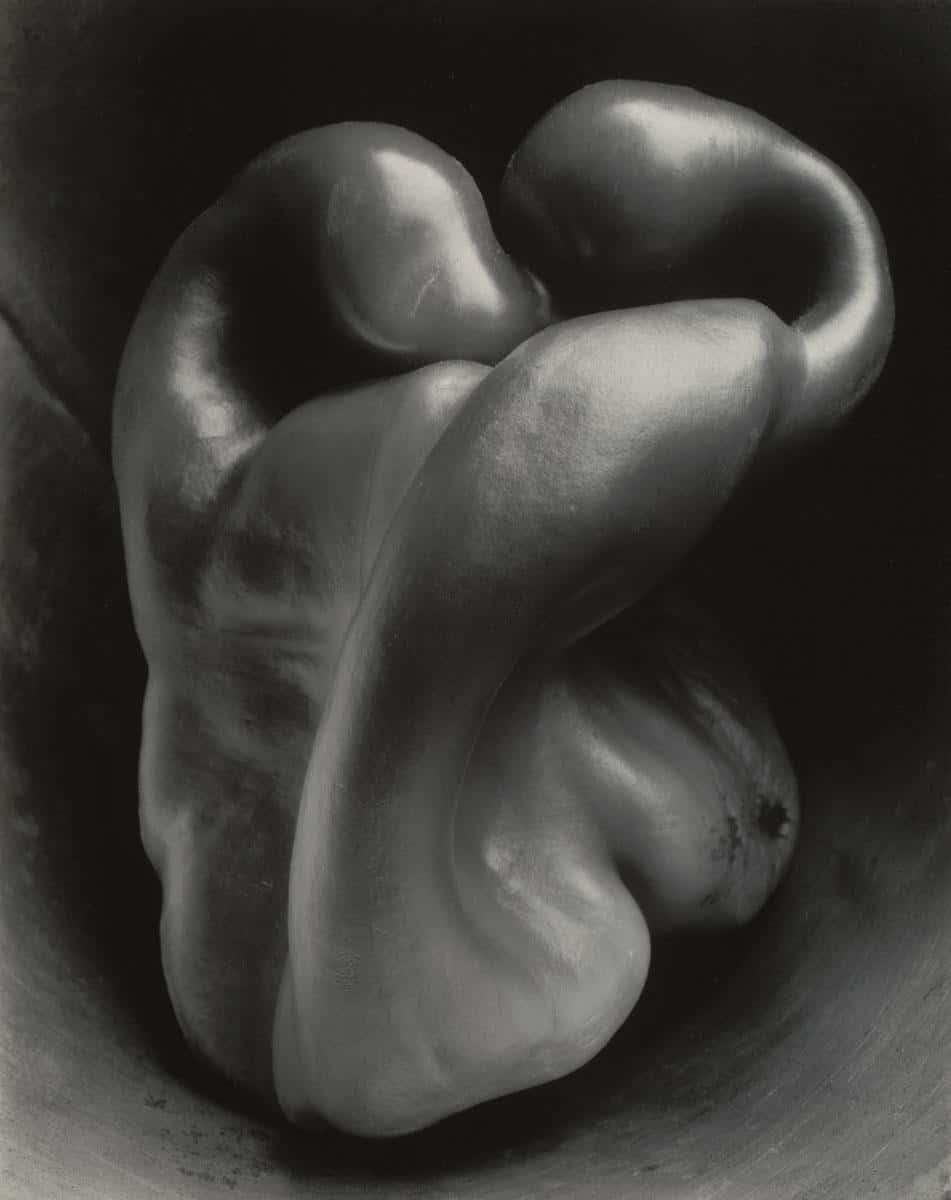

The form is a singular or collective subject(s) expressed as a shape in volume taking into account light and shadows, its three dimensions. When it comes to composing subjects, trained artists have a set of tools to employ, with a background in sketching and sculpture they have an innate ability to distil from chaos. Hours of reductive sketching have heightened their sensibilities to recognise and shape a subject to find a composition and make an interesting image.

The human brain can assimilate a multitude of visual clues in three dimensions including beyond the area of the immediate subject in front of us. The camera frame is a cyclops view of one narrow field that ultimately presents in 2D. As photographers, we have to develop our ability to bridge that gap and to see how the camera’s optics ‘see’. One approach I use for pre-visualising a scene in 2D is closing one eye to evaluate its potential before even taking the camera out of its bag.

We often arrive back home after a trip, upload our photographs and find we are underwhelmed by how they look. No composition, certainly not as we imagined on location; they just don’t stand out or work as strong images.